By Joseph Kandel, M.D.

When I see a patient for the first time and mention to them I feel they may have Parkinson’s or a related condition, that is the last thing the patient hears. They think that their life is over, they won’t be able to get out of the bed or the wheelchair, and won’t be able to talk or communicate. That is the farthest thing from the truth. Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects a certain part of the brain, and leads to a movement disorder. It is a human condition, certain cells of the brain stop producing a chemical, dopamine, that is very important in movement. I explain to patients that anyone that lives long enough will likely have this process, and then try to go on to educate the patient regarding the disorder.

When I see a patient for the first time and mention to them I feel they may have Parkinson’s or a related condition, that is the last thing the patient hears. They think that their life is over, they won’t be able to get out of the bed or the wheelchair, and won’t be able to talk or communicate. That is the farthest thing from the truth. Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects a certain part of the brain, and leads to a movement disorder. It is a human condition, certain cells of the brain stop producing a chemical, dopamine, that is very important in movement. I explain to patients that anyone that lives long enough will likely have this process, and then try to go on to educate the patient regarding the disorder.

There are four types of Parkinsonian syndromes, and these are primary or idiopathic (which means as a physician we don’t know the cause of the disorder), secondary or acquired, hereditary, and Parkinson’s plus syndrome (multiple system degeneration). The most common form is the idiopathic version.

Parkinson’s is a movement disorder. The classic features include stiffness, slowness, rigidity, and tremor. Balance issues, including falling over backwards (“retropulsion”) is also frequently seen. Often a patient will demonstrate the classic Parkinson gait, which is an individual walking with a stooped or bent over posture, and a lack of arm swing. Because their center of balance is forward and they have a hard time adjusting their movements, they often have a shuffling type of gait which is called festination. Spouses of patients with Parkinson’s will frequently state they have to tell the patient to “stand up straight”.

There are other symptoms which can be seen in this condition, including difficulties with speech and swallowing (hypophonia, dysphagia), difficulties with writing, often with a small, chicken scratch type of signature or writing (micrographia), as well as a variety of cognitive and mood issues. Issues with concentration, executive functioning and planning, memory and slowed cognitive speed can all be seen with this disorder. There is a higher risk of dementia in individuals who have been given this diagnosis. Not surprising, many patients will develop anxiety or depression. In addition, individuals will often have a sleep dysfunction, as they have a hard time turning themselves from side to side and will awaken frequently throughout the night. They may have issues with additional aspects of their nervous system, in particular controlling blood pressure, sweating, and their bowel or bladder.

Establishing a diagnosis:

The diagnosis is made with a clinical examination. I often explain to my patients that I can walk into any mall and pick out the five or 10 people with Parkinson’s in one or two minutes. However, it takes me much longer to examine the patient and convince them that I know what the disorder is and what the best approach to treatment will be. On the examination I will often find increased tone, stiffness, and rigidity. Speech, appearance, slowness of movements, and imbalance can also reveal the diagnosis. Often an MRI or CT of the brain will be ordered, to rule out any other type of problem that could cause similar symptoms. If there is a cognitive change, an EEG may be appropriate. Laboratories to rule out reversible causes of cognitive decline may be helpful. More recently, there is a diagnostic test, the DAT scan, which can reveal a pattern of reduced dopamine activity in the basal ganglia and this certainly aids in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease.

How is this treated?

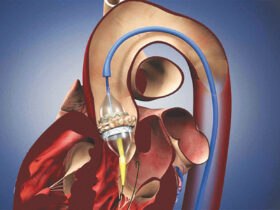

There is no cure for this disorder. However, medications, include levodopa (replacement chemical for what the brain is no longer making), dopamine agonists (boosters that help the levodopa), and MAO-B inhibitors (prevent breakdown of Dopamine) can all be effective. Many other medicines play a secondary role. There is also brain surgery, particularly deep brain stimulation, which is most beneficial for those whose disorder includes tremors and motor fluctuations, poorly controlled with medications.

What is the role of exercise

and treatment?

I educate my patients that this is essential. Only a small percent of the medication crosses the blood-brain barrier, but this increases when the patient does aerobic exercise. In addition, the brain does something amazing, called up regulation. There is a significant increase in the number and activity of the dopamine receptors. I often explain to my patients that one pill can often act like nine pills, with quite a bit less side effect.

If you or someone you love may have Parkinson’s, contact the Neurology Office, Joseph Kandel, M.D. and Associates, to find out what you can do to start on a healthier journey!

To see the expert therapy team at Neurology Office, call to make an appointment with Dr. Kandel 239-231-1414 (Naples) or 239-231-1415 (Ft. Myers) or check out the web site: www.NeurologyOffice.com