By Lam Nguyen, MD, Orthopedic Spine Surgeon

Clinically significant osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (VCF) accounted for 52,000 hospitalizations per year in the US. In the US in 2005, there were over 2 million fractures at a total cost of 17 billion USD. Of that total, vertebral osteoporotic fractures accounted for 6% or 1 billion dollars. By 2025, the annual number of fractures is projected to increase by 50%, costing over 25 billion USD.

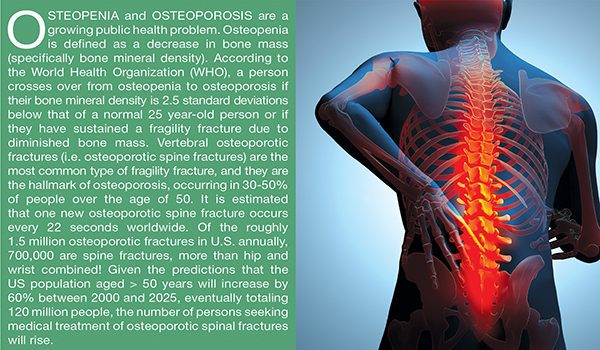

Osteoporotic fractures have a significant impact on a patient’s function and quality of life.

Moreover, osteoporotic vertebral fractures have a considerably greater and more prolonged impact on health-related quality of life than do hip and other fragility fractures.

Pain and deformity results in decreased mobility and decreased tolerance of activities of daily living. Less activity results in further bone loss.

Together, the change in posture, balance and gait mechanics and further bone density loss from decreased activity predisposes to falls and additional fractures.

People who develop an osteoporotic compression fracture in the spine are at risk for developing additional fractures, with a 5 fold increase risk after the first compression fracture and up to 75 fold increase after 2 or more fractures. Lung function is also significantly reduced in patients with osteoporotic thoracic and lumbar fractures.

The loss of height and thoracic space created by the kyphotic deformity (humped back deformity) leads to a secondary decrease in lung space. Studies have shown that the degree of kyphosis is related to the risk of pulmonary death in these patients. In addition to the physical disabilities, these patients suffer psychological ramifications of low-self esteem, anxiety, depression, and social isolation.

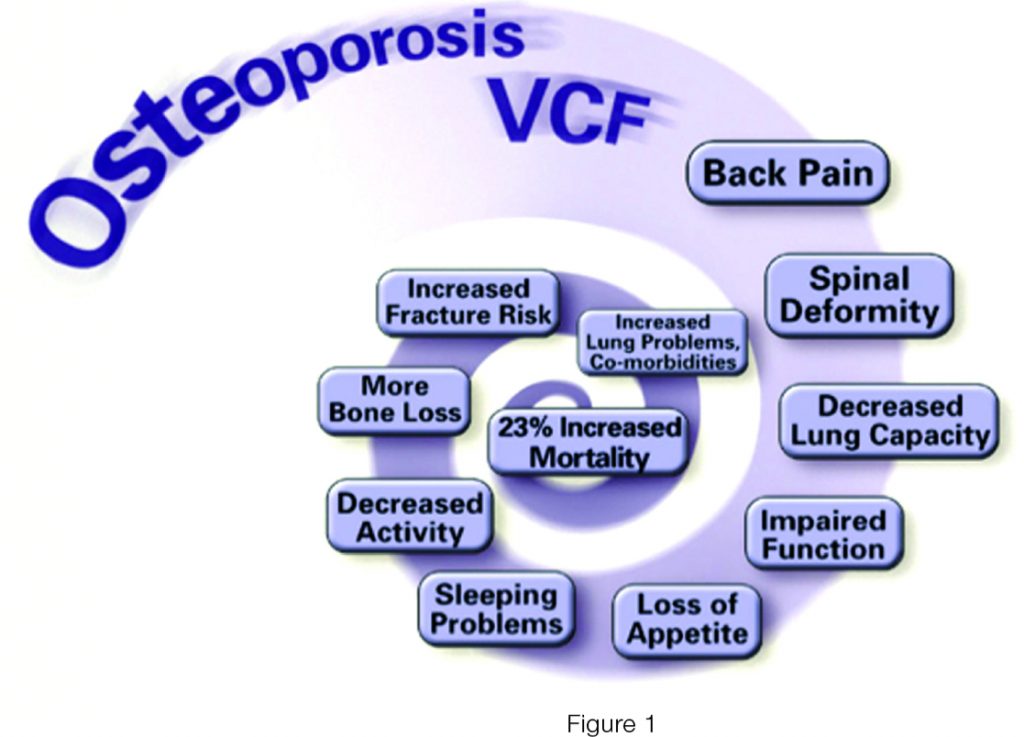

There is no doubt that osteoporotic spinal fractures are associated with an increased risk of mortality. Researchers have conducted a review of Medicare claims from 1997 through 2004 and they found that an elderly patient with a vertebral compression fracture had almost two times the risk of death compared with an elderly person without a vertebral compression fracture. In a different study, these authors reported that the relative risk of dying is highest following a spinal osteoporotic fracture, even higher than following a hip fracture. These are not discrete problems. Once an osteoporotic vertebral fracture occurs, there is a cascade of events that occurs long-term that ultimately leads to an increased rate of mortality (Figure 1 ).

Prevention and treatment of osteopenia and osteoporosis is the key to the management of vertebral compression fractures. If you have had a spinal compression fracture or any type of fragility fracture, you should discuss with your primary care physician about getting evaluated for osteopenia or osteoporosis.

The initial workup typically consists of basic lab tests and a Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry scan (DEXA scan), which is a specialized x-ray scan, to measure your bone density. If testing reveals decreased bone density, treatment should be initiated. Your calcium and vitamin D levels should be checked and treated with supplementation if found to be deficient. You should talk with your primary care physician, or an endocrinologist, to decide which treatment option is the best for you.

Once an osteoporotic spinal compression fracture has occurred, the mainstay of treatment for vertebral compression fracture remains non-operative (temporary bracing, activity modification, and pain medications) as many of these patients get better with time. However, for a small subset of patients, the shortcomings associated with non-operative management may mitigate any potential efficacy.

Activity modification or reduction may further advance bone loss. Pain medications can cause many potential side effects without adequately relief pain. Orthotics are costly and sometimes poorly tolerated by the elderly.

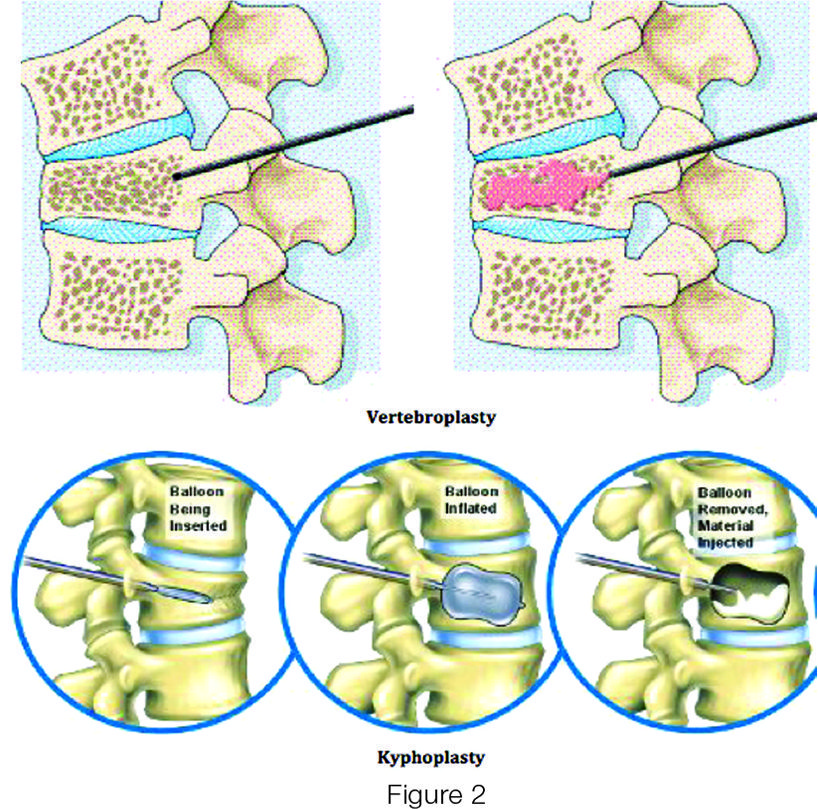

For patients who have failed to get better with non-operative management after 6-12 weeks, percutaneous cement augment procedures remain a good option. Cement augmentation is a common procedure, with as many as 75,000 performed annually in the Medicare population in the United States. The two described techniques are vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty (Figure 2).

Vertebroplasty is performed through a needle that is inserted into the vertebral body. Liquid cement, which rapidly hardens, is injected under pressure to fill the fractured vertebral body. Kyphoplasty

is performed in a similar fashion, but an inflatable balloon is used to create a space inside the vertebral body into which the cement is filled. These procedures are performed on an outpatient basis, and patients go home the same day. Multiple search studies have shown that cement augmentation procedures result in significant pain relief, functional recovery, and improvement in quality of life for patients who have failed a trial of nonoperative treatment.

For more information for their services and organization, please visit their website at www.Kwoc.net.

941-893-6447