By Nicholas Franco, M.D., Board Certified Urologist –

Hematuria can be divided into two categories. Gross hematuria and microhematuria. Gross hematuria is visible blood in the urine with or without blood clots and may range from a blush color to dark red. Microhematuria is blood found on urinalysis that is not visible. Although a urine dipstick test may read positive due to several food or drug metabolites, a true finding of microhematuria is defined as greater than two red blood cells per high-powered field in the absence of excess squalors epithelial cells, which are often seen on a contaminated or “nonclean-catch” specimen. Urinalyses are often performed as part of routine history and physical examination and must not be overlooked. When found, the primary care physician must decide first of all if it is a good specimen and then decide how to proceed.

Hematuria can be divided into two categories. Gross hematuria and microhematuria. Gross hematuria is visible blood in the urine with or without blood clots and may range from a blush color to dark red. Microhematuria is blood found on urinalysis that is not visible. Although a urine dipstick test may read positive due to several food or drug metabolites, a true finding of microhematuria is defined as greater than two red blood cells per high-powered field in the absence of excess squalors epithelial cells, which are often seen on a contaminated or “nonclean-catch” specimen. Urinalyses are often performed as part of routine history and physical examination and must not be overlooked. When found, the primary care physician must decide first of all if it is a good specimen and then decide how to proceed.

The following is a description of an appropriate approach to this condition: Hematuria is caused by four major categories of problems. These include infection, urinary calculi, trauma to the urinary tract (either mechanical or physiological/drugs/toxins) and neoplasm. It is estimated that up to 26% of cases of microscopic hematuria in adults result from significant urological pathology, including cancer. It is, therefore, critical to consider urological referral for evaluation. The incidence is even higher in patients who smoke tobacco.

Once hematuria is confirmed and infection is ruled out, it is important to note that the resolution of the hematuria does not eliminate the need for urological evaluation. For example, a papillary transitional cell carcinoma within the bladder or kidney may bleed at times, and then not bleed again for months. The observation of hematuria may prevent a delay in diagnosis of this very curable condition.

Proper evaluation of a patient with hematuria includes both upper and lower urinary tract survey. These protocols are well established and may be fine tuned by the urologist after referral.

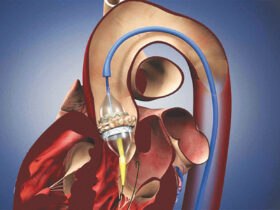

The following is a general description of the typical standard hematuria workup: The kidneys must be evaluated for tumors of the parenchyma as well as the connecting system and also be checked for stones or obstruction or malfunction. Therefore, renal ultrasound alone is NOT enough. A study that includes contrast of the upper tracts is imperative. For patients with normal renal function, the most useful test today is the CT urogram, which provides three-dimensional images of the entire urinary tract with and without contrast as well as an anterior-posterior excretory phase, which demonstrates the entire collecting system and can be used to rule out tumors within the renal collecting system or ureters. The intravenous pyelogram may also be used for this, but must include nephrotomograms to rule out renal masses. If a patient has renal insufficiency or has a severe allergy to intravenous contrast, either a renal ultrasound or non-contrasted CAT scan may be used in conjunction with retrograde pyelograms (RPGs) performed by the urologist. RPGs are performed by placing a small tube into each of the ureteral orifices and then obtaining x-rays before, during and after injecting contrast into the renal-collecting systems.

In addition to evaluation of the upper urinary tracts, the bladder and urethra must be evaluated by cystoscopic examination. Cystoscopy is a minor procedure performed in an outpatient setting under local anesthesia or mild IV sedation. The urologist passes a flexible fiberoptic scope into the urethra and bladder to visualize the entire lining as well as to make observations regarding the size and shape and level of obstruction from the prostate gland in males.

Bladder washings for cytological evaluation as well as a fluorescence in situ hybridization test (FISH) on a voided urine sample are also part of this evaluation. The FISH test allows for the identification of cells with genetic abnormalities that are linked to the development of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder or kidney and is very sensitive while the standard cytology tests done on bladder wash at the time of cystoscopy is more specific. Both should be done to complete the hematuria evaluation.

In summary, hematuria is a very common finding and microhematuria may be the only sign of significant underlying urological disease in a significant number of patients. Resolution on repeat urinalysis a week or two later does not rule out these conditions. Hematuria should be confirmed on a clean catch or catheterized specimen and infection should be ruled out. Urological evaluation is imperative once it is confirmed and includes a specific battery of testing procedures that will identify causes and provide for early intervention when necessary.

Specialists in Urology

239-434-6300

www.specialistsinurology.com