Part one of a series

Pain is often progressive and over time, it can become unbearable and debilitating for many individuals. Understanding pain and its root cause is essential for optimal treatment. The four areas of pain are stability, articulation (joint), neuromuscular, and symmetry. If you have chronic spinal pain of almost any type, from spinal arthritis to nerve pain and sciatica, you will be forever at its mercy if you don’t understand its four parts.

Pain is often progressive and over time, it can become unbearable and debilitating for many individuals. Understanding pain and its root cause is essential for optimal treatment. The four areas of pain are stability, articulation (joint), neuromuscular, and symmetry. If you have chronic spinal pain of almost any type, from spinal arthritis to nerve pain and sciatica, you will be forever at its mercy if you don’t understand its four parts.

PART ONE: STABILITY

Stability: Your spine is made up of individual segments that stack on top of each other like kids’ building blocks. This is by its very nature an unstable mess. You have all sorts of systems designed to keep it all from falling apart and being sloppy. The spine joints may have a small amount of extra motion that is literally slowly destroying them. The real shocker is that many highly trained physicians and surgeons will likely never tell you about this instability, nor do many understand it themselves as they selectively focus in on their specialty. More concerning is that it can generally be fixed with a few simple injections or exercises.

Take this short quiz to see if this section applies to you. If you answer any question with a yes, you may have a spinal stability problem.

1. My back or neck gets very sore or swollen after I exercise. Y N

2. I hear cracking/popping in my back or neck when I do certain activities. Y N

3. My back or neck feels like it’s loose or moves too much. Y N

4. My head gets heavy by the end of the day. Y N

5. My arms or legs tingle or get numb when I’m active or when I sleep. Y N

What does it mean to be stable? Stable in a mechanical sense means resistance to falling apart or falling down. For your body, joint stability is a very big deal, yet you likely haven’t been told the whole story. You see, you’ve only been told about a very unstable joint that requires surgery to fix a completely torn and retracted ligament. Yet it’s the instability you don’t know about that’s slowly frying your spine, one movement at a time. Discovering which areas have this kind of instability, called sub failure, may save you from spine surgery.

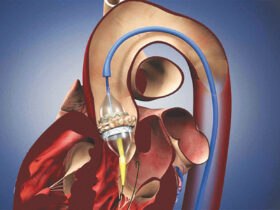

What is sub-failure instability, and how do you know if you have it? Sub failure instability means that the levels of the spine aren’t kept in exact proper alignment during movement. Important? When the individual spine bones uncontrollably crash into one another or even just can’t be kept in alignment, the nerves can get pinched and the discs and facets joints wear down much faster. An unstable part of the spine literally experiences many times the wear and tear of a stable spine, and bone spurs form. Since stability in many joints is the number one determinant of whether that joint will have a long happy life or become “old” before its time, it’s a wonder more time isn’t spent assessing this component of joint health.

Let’s breakdown spine stability by separating the type you’ve heard of and that is usually easily diagnosed, from the type that will slowly destroy your joints and will likely never get diagnosed. There are two major types of instability: surgical and sub failure. Surgical instability is less common than its more prevalent cousin—sub failure instability. However, surgical instability is usually the only type that the orthopedic-spine surgery establishment treats. This means that a spinal level is very unstable and unable to hold itself together at all. In these cases, surgery is often needed to stabilize the joint.

Examples would be severely damaged ligaments in the spine, where a spinal cord injury is feared if the spine isn’t surgically stabilized. A true surgically unstable spine may need a fusion where the bones (vertebrae) are fused together with additional bone

Sub failure means that the ligament hasn’t completely failed (torn apart like a rubber band), but instead it’s only partially torn, degenerated, or just loose. This much more common type of instability often doesn’t require surgery and is characterized by small extra motions in the spine just beyond the normal range. In fact, if you have this type of instability, you likely aren’t aware you have this problem, so while we have some diagnostic tests to detect this type of instability, our understanding of what is normal and abnormal is only now coming into focus. However, this type of instability is quite real, and it’s a clear and long-term insidious drag on spine health.

More on Sub failure:

It’s All About Your Ligaments and Your Muscles There are two types of sub failure instability: ligament and muscular. Passive ligament stability keeps our spine bones from getting badly misaligned. Think of ligaments as the living duct tape that holds the spine together. Without these ligaments, every step would cause the spine bones to experience a potentially damaging shift. On the other hand, active muscular stability is made up of the firing of deep multifidus muscles that keep the spine bones aligned as we move and represent the stability fine-tuning system. The spine building blocks tend to want to slip slightly out of alignment as the spine bends, twists, or slides, even with intact ligaments. As this happens, signals are sent to selective muscles that surround each level of the spine (multifidus) so that they adjust and correct the alignment. Without this active system, the spine would be “sloppy.” This muscle firing is a muscular symphony, with microsecond precision being the difference between the poetry of beautiful movement and an asynchronous chorus of potentially damaging spine bones colliding against one another.

So what do the muscles do again? The muscles provide the fine-tuning. They act as constant stabilizers for the joint, keeping it in good alignment while we move. This small area where the joint must stay to prevent damage as we move is called the “neutral zone.” So in summary, stability is about both muscles and ligaments. Your deep multifidus muscles provide constant input to the joint to keep the spine bone alignment fine-tuned as we move. When the spine bones move too much, the ligaments act as the last defense to prevent joint damage from excessive motion.

The Spine is a Marvel of Stability Engineering The spine is advanced engineering. The spinal column is a series of blocks that stack one upon the other and provide a base of support for the extremities and protect the spinal cord and nerve roots. These interlocking blocks (vertebrae) use the same stability model as described above— muscles and ligaments. Now let’s look at how the spine stays stable. What happens when you place a bunch of blocks one on top of the other? This tower of blocks gets less stable as the pile gets higher. One way to stabilize this high tower of blocks would be to tape the blocks together. This would make the blocks more stable but wouldn’t allow much motion. You could use more flexible tape than duct tape or Scotch tape, but again you’d either end up providing too little stability (highly elastic rubbery tape that gives a lot when you stretch it) or too much (duct tape or Scotch tape that’s more rigid). The right kind of tape (ligament) would likely allow this motion, but the individual blocks would still start to shift against each other. This shifting could result in disaster, as the spinal cord runs through a hole (spinal canal) inside the blocks, and the spinal nerves exit between the blocks through a special bony doorway (foramen). As a result, too much movement between the blocks means nerve damage or, worse, a spinal cord injury. This is the dilemma of the spine—how to stack lots of blocks (about 25 high in most people) while keeping the whole thing stable and flexible as you move and at the same time protecting the nerves. Is there a solution? YES>>> Please read the remainder in next month’s series

Florida Pain Center

(239) 659-6400

info@flpaincenter.com

730 Goodlette Rd North, #200, Naples, FL 34102