By Lam Nguyen, MD, Orthopedic Surgeon

The cervical spine (neck) is made up of a series of connected bones called vertebrae. The bones protect the spinal cord that runs through the spinal canal. The spinal cord contains nerves that give strength and sensation to the arms and legs, and provide bowel and bladder control. With age, the intervertebral discs (the shock absorbers between the vertebrae) become less spongy and lose water content. This can lead to bulging of the discs into the spinal canal, resulting in narrowing of the spinal canal. The bones and ligaments of the spinal joints also thicken, further contributing to the narrowing. These changes are common after age 50 and are generally called “cervical spondylosis” (neck arthritis) or “cervical stenosis” (narrowing of the neck spinal canal).

The cervical spine (neck) is made up of a series of connected bones called vertebrae. The bones protect the spinal cord that runs through the spinal canal. The spinal cord contains nerves that give strength and sensation to the arms and legs, and provide bowel and bladder control. With age, the intervertebral discs (the shock absorbers between the vertebrae) become less spongy and lose water content. This can lead to bulging of the discs into the spinal canal, resulting in narrowing of the spinal canal. The bones and ligaments of the spinal joints also thicken, further contributing to the narrowing. These changes are common after age 50 and are generally called “cervical spondylosis” (neck arthritis) or “cervical stenosis” (narrowing of the neck spinal canal).

Stenosis (narrowing or pinching) does not necessarily cause symptoms. However, when the narrowing becomes symptomatic, patients may present with symptoms of cervical radiculopathy (nerve root dysfunction) and/or cervical myelopathy (spinal cord dysfunction). Patients with cervical radiculopathy (nerve root dysfunction) often present with pain radiating from the neck down the arm to the hands and fingers with or without tingling/numbness and weakness. On the other hand, patients with cervical myelopathy (spinal cord dysfunction) often present with painless, insidious decline in function of the arms and legs, gait unsteadiness, and loss of bowel or bladder control.

Loss of hand dexterity is frequently encountered in myelopathic patients. Common complaints can include dropping of light objects, changes in handwriting, inability to discern coins when removing change from one’s pocket, difficulty in buttoning a shirt, or fastening the clasp of a bra.

Gait disturbances are also common in patients with cervical myelopathy. It is not unusual that a spouse or other relative notices the gait problem in advance of the patient’s own awareness. Patients typically present with gait unsteadiness, trouble going up or down stairs, or new onset or an increase in the frequency of falling down. With advanced disease, an increased requirement of ambulation aids such as a cane or walker can occur. Although very rare, confinement to a wheelchair can be the end result of progressive ambulatory dysfunction due to cervical myelopathy.

The evaluation of patients suffering from cervical myelopathy requires diligence and attention to detail to avoid delay in diagnosis. Patients often downplay the gait disturbances and loss of hand function as part of getting older. Symptoms that may be related to the myelopathy but have previously been attributed to other diagnoses should be revisited. For example, although rare, patients with cervical myelopathy have been mistakenly diagnosed with Parkinsonism or other neuro-degenerative disorders, or an inner ear problem causing gait imbalance by a physician who is not familiar with spinal disorders.

Along with a thorough physical examination, MRI and/or CT scan are the best imaging tools to diagnose cervical myelopathy. Xrays alone are inadequate. MRI images are very detailed and show the tight spinal canal and pinching of the spinal cord. MRI can show signal changes within the spinal cord, suggestive of severe pinching of the cord. A computed tomography (CT) scan may give clearer information about bony invasion of the canal and can be combined with an injection of dye into the fluid around the spinal cord and nerves (CT myelogram). Electrical studies may be used to distinguish between myelopathy and other conditions. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction velocity (NCV) may help rule out peripheral nerve problems that can mimic cervical radiculopathy and myelopathy.

The natural history of cervical myelopathy is highly variable, but it is generally that of progressive decline in function separated by periods of stability (no change in symptoms). Mild cases of cervical myelopathy may be amenable to nonoperative treatment. Nonsurgical treatments do not change the spinal canal narrowing, but may provide improvement in life function via pain control with medications and functional rehabilitation through physical therapy. Patients are often advised to return to clinic every 3 to 6 months for repeat evaluation to closely monitor for neurologic decline.

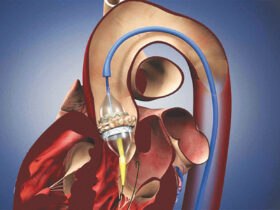

In cases with worsening deficits such as increasing clumsiness or weakness, pain or the inability to walk, surgical treatment is usually recommended. The main goal of surgery is to prevent worsening of the symptoms. Surgical options include anterior decompression and fusion, where the disc and bone material causing spinal cord compression is removed from the front and the spine is stabilized. The stabilizing of the spine, called a fusion, places a bone graft (implant) between cervical segments to support the spine and compensate for the bone and discs that have been removed. Often, your surgeon may choose to add a small metallic plate and screw fixation device for increased stability.

Another surgical option, laminectomy, involves removal of bone and ligaments pressing on the spinal cord from the back of the neck. In some cases, your surgeon might add a fusion to stabilize the spine as well. A second option, called laminoplasty, involves expanding the spinal canal from the back of the neck. A laminoplasty is a motion-preserving surgery as no fusion is performed. In this procedure, part of the bony arch is removed and a hinge created. This hinge is “opened” to increase the room for the spinal cord.

Several factors are considered by your doctor when choosing your surgical procedure. Typically, these include the alignment of your spine, location of the compression (front or back), quality of your bone, number of levels involved and your overall medical status. Based on these factors, your doctor may recommend anterior, posterior or combined approaches.

Kennedy-White Orthopedic Center

For more information on their services and organization, please visit their website at www.Kwoc.net.

941-893-6447

ABOUT DR. NGUYEN

Lam Nguyen, MD – Orthopedic Surgeon, Spine Surgery

Dr. Lam Nguyen is a fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeon who specializes in spinal surgery. Following his undergraduate studies at Duke University, where he majored in psychology, he attended medical school at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine at Chapel Hill. He was inducted into his medical school’s John B. Graham Research Society. Dr. Nguyen subsequently completed his Orthopaedic Surgery Residency at Loyola University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. During his residency, Dr. Nguyen investigated the effect of cervical spine alignment on spinal posture and biomechanics. The results of his research have been published in peer-reviewed orthopaedic journals and presented at multiple national and international scientific meetings. Dr. Nguyen was also awarded the distinguished title of “Chief Orthopaedic Resident” during his last year of training.

After his residency training, Dr. Nguyen pursued a one-year fellowship in spinal surgery, where he trained with nationally and internationally renowned spine surgeons at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, Oregon. Dr. Nguyen specializes in the comprehensive care of spinal disorder, from the cervical spine (neck) to the sacrum (tailbone). This includes degenerative conditions (disc herniation and stenosis), as well as spinal deformities (scoliosis and kyphosis), spinal trauma and instability, spinal infections, and metastatic spinal tumors. Dr. Nguyen also has experience in minimally invasive spinal decompression and fusion, cervical disc replacement, and complex revision surgery. The diagnosis and treatment of spinal conditions is a complex process, and Dr. Nguyen relies on a thorough assessment to recommend the right surgery for the right patient. In an era when medical decision is largely based on laboratory results and imaging findings, Dr. Nguyen still believes in the art of medicine: correlating patient symptoms with objective study results and offering the appropriate treatment solutions. He understands the stress and challenges facing the possibility of surgery and aims to help patients achieve a peace of mind in understanding their problem. He takes pride in listening to patients, and helping them formulate an individualized plan that is based on high quality science and cutting edge technology. Dr. Nguyen finds satisfaction in guiding patients through surgery toward their fullest potential recovery.

Dr. Nguyen is a published scholar, having authored a dozen peer-reviewed articles and multiple book chapters since 2006. He is a member of several spine surgery societies, including the North American Spine Society, the International Society for the Advancement of Spine Surgery, and AO Spine North America.

In his free time, Dr. Nguyen enjoys spending time with his wife who is a child and adolescent psychiatrist, traveling, and cooking.

For more information on their services and organization, please visit their website at www.Kwoc.net.

941-893-6447